Traces of Drawings - A selection of Lebanese artwork

Introduction and extract of the book Traces of Drawings - A selection of Lebanese artworks - Nabu Museum - Contact Nabu Museum to get the full book.

Gibran Khalil Gibran's words about Suleiman al-Boustani published in Al-Saeh newspaper in 1925 have come to our minds. He wrote after drawing his friend on his deathbed: “…When Suleiman al-Boustani passed away, I stood alone in front of his coffin and cried to myself, assuming that I had lost a beloved friend. Yet, I saw my friend standing with two eternal stars in his eyes…”

Art, whether painting, sculpture, music, cuneiform tablets or monuments of creative people from Ebla in Syria to the epic of Gilgamesh and Tyre and Jbeil confirm that they are immortal, and here is NABU telling us that ideas never die. These artists and their works, whatever we call them and however we describe them, are neither classical, nor abstract, nor impressionists, nor cubists, nor Lebanese nor… and yet they are all of this and as such they will survive us.

In a region of seemingly constant turmoil and strife, “NABU” Museum is both a space for art and an institution for preserving and enhancing culture, reaching out to communities through education and training programs, public lectures and guided exhibits. We aim to produce and develop art practices in the region to reflect our contemporary realities. By providing a platform for encounter and cultural exchange and by supporting local art production we hope to challenge various audiences in a modern and creative way.

If we revisit the 20th century, history reveals to us the magnitude of the calamities inflicted and how they cast their shadow on the 21st century. From the Balfour Declaration, the Palestinian tragedy, the massacres of two world wars, the wars of domination in East Asia and South America, the atomic bombs in Japan, to the Lebanese Civil War, and the Middle East wars of destruction and the looting of Iraqi and Syrian antiquities, a sequence of man-made horrors whereby the world emerges as a series of migrations, exile, and imprisonment. Thus, art and artistic production become not only an embodiment of reality and suffering but a form of resistance against exile, resistance against the wars of destruction and uprooting, which may help us establish a new place for belonging and more importantly, make the homeland we dream of through words and images.

NABU Museum founders

Fida' Jdeed, Badr el-Hage, Jawad Adra

Traces of Drawings

A selection of Lebanese artwork

Drawing - whether for the purpose of recording reality, achieving technical artistic mastery, communicating the intention of the artist in the execution of the final artwork, mapping out ideas or producing a finished artwork - is considered a creative attempt to make sense of the world around us.

This exhibition demonstrates the many ways that drawings are faithful testimonies of artistic practices. They represent the artist's attempt to finding creative activity within art history. Starting with Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate under the Ottoman Empire to the French Mandate, Independence, and the establishment of the first Fine Arts institutions in Lebanon, moving forward to the rise of art gallery culture in Beirut in the 1960s, to the civil war and beyond, “Traces of Drawings” takes the viewer on a journey. It starts with the fragile and rarely shown academy drawings such as the meticulously rendered anatomical studies by the pioneer modern master Daoud Corm. The exhibition moves on form classical drawing techniques to ideation drawings as modular thinking processes and complex equations of DNA studies translated into Saloua Raouda Choucair's sculptures, followed by Etel Adnan's drawn poems, Laure Ghorayeb narrative doodles, and wraps up with Grata Naufal's artwork. Some other important artists have not been covered in this catalog for logistical reasons.

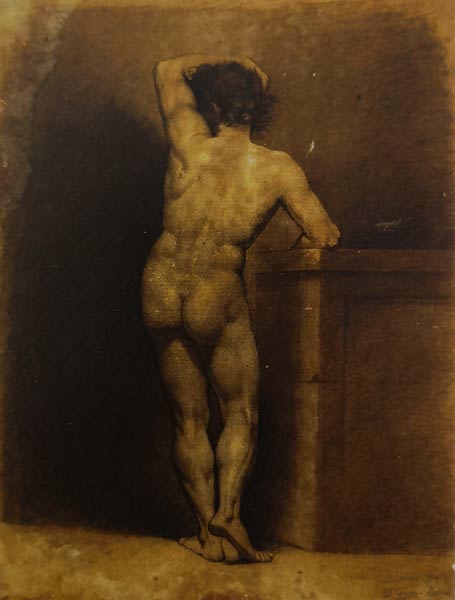

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, in the classical academy of the beaux-arts, drawing was regarded as the foundation of artistic practice. Accurate reproductions of landscapes and figurative drawings were the mission of old masters. For Daoud Corm and his successors - Youssef Howayek, Habib Srour, Moustapha Farroukh, Omar Onsi, Saliba Douaihy, and Cesar Gemayel - anatomical drawing was considered a certificate for demonstrating the artists' craftsmanship. Learning how to draw meant mastering common poses to expand the artist's understanding of how the body looks when in movement. It required learning the position of ligaments in relation to the skeleton and the muscle structure of the human body. The mastering of light and shadow in a drawing was also considered proof of the artist's classical training in the academy following the Renaissance masters. Mechanical drawings, as seen in Farroukh's preparatory drawings, helped in defining perspective and refining the composition. While Farroukh's sketches reveal an overall plan for the division of space, Onsi prefers to start with repeated small croquis, detailed studies of cactus drawings that are later integrated within the overall painting composition.

While looking through the evolution of the depiction of the human figure in the arts of Lebanon, it is worthwhile noting that the nude figure in the practice of drawing did not only demonstrate the artist's knowledge and aesthetic sensibility, but it also symbolized an entry to al-asr al-hadith, or modernity. Moving forward, one can trace a trajectory that starts with the human-as-god figure to the human-as-machine figure. The evolution of drawing of the human body in the tradition of the beaux-arts education as seen in the drawings of Corm, Howayek, Srour, Farroukh, Onsi, Douaihy, and Gemayel is broken down into geometrical interlocking shapes that appear as an intriguing juxtaposition of overlapping man-machine figures, which appear in Guiragossian's painting. This man-machine representation, developed by the artist, in small gouache drawings resonates with the anxiety experienced in Europe's mechanical age in the 1930s and 1940s.

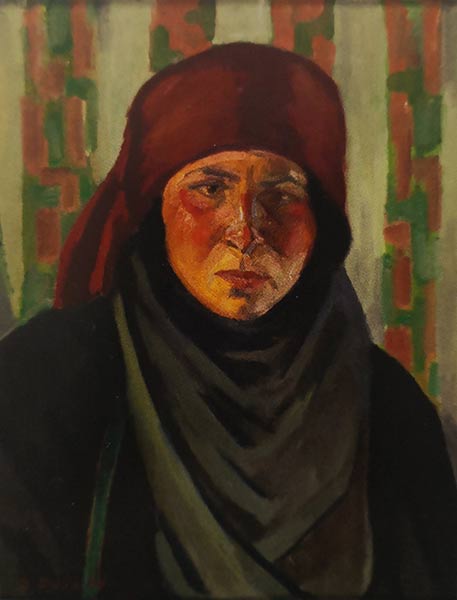

The second part of the exhibition includes a selection of drawings that were produced after the establishment of the Academie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts in 1943. During this period, the classical academic drawings were no longer appealing. A growing number of artists started experimenting with new material and techniques in search of distinctive styles. Their drawings gradually evolved from academic realism to figurative and non-figurative abstraction. This shift is seen in Choucair's modular painting, el-khal's monolithic compositions, Jurdak's vibrant color abstractions, Afaf Zurayk's poetic Human Form series and many others. “Two things interest me,” explains el-khal, “the human face and color. Each has its own living presence, its own spirit…” Fascinated by color, she developed her figurative drawings into abstract monochromatic ethereal compositions. These drawings gradually disengage with lines and forms to incite emotions and thoughts that are waiting to be read as new narratives unfold.

When the drawings are no longer mimetic or derivative of reality, forms take on new meanings following particular knowledge, composition, and content as seen in Jamil Molaeb and Rafic Charaf's work. In line with this new approach, Saliba Douaihy explains: “art is creation and not the imitation of nature. Nature is one thing and Art, another.” This shift in representation and the practice of drawing does not rely on copying nature, but rather pushes the artist to experiment in drawing techniques. This is striking when it comes to Yvette Achkar's abstract still life compositions and Aref el Rayess's soft renderings of rocks that brought forth his own vision of the desert landscape.

Farid Aouad's drawings in the café and metro spaces around Paris are considered examples of drawings as finished artwork. Instead of documenting his urban experience in writing, Aouad opted to draw. Scribbling was his technique in depicting the rapid pace of urban life as it is happening. While Aouad looked for lines of movement in describing what he saw, Shafic Abboud developed abstract forms, windows, as a starting point for his narrative drawings. Looking inward and outward at the same time, he used these windows as metaphors for his inner journey. On the other hand, Amin el-Bacha, whose playful mind never ceases to surprises us with unresolved riddles and other hand, Amin el-Bacha, whose playful mind never ceases to surprise us with unresolved riddles and other visual tricks, draws a mise-en-abime of himself in the space of his studio, thus breaking the traditional form of a self-portrait drawing.

This exhibition also includes drawings that were made during the Civil War in Lebanon (1975-1990). During this period, drawing was an escape or a refuge for artists to express their distress. It took a different turn to become a tool for the artist to tell stories of the warlike fragments within a narrative. Violent brush strokes and dripping paint is often seen in Jean khalifé and Nabil Nahas's drawings of the war. For Seta Manoukian, it is through the distorted spaces in her “Hospital” series of drawings that she depicts the brutal realities of the war. Manoukian drew the portraits of wounded civilians lying in their hospital beds while Khalifé drew exile and migration. It is in Naufal's drawings of life in the shelter” - later transcribed on her large mural -that we gain an insight of the daily life as experienced by the artist, her family, friends, and neighbors sharing the same shelter during the massing bombing of Beirut. As words would convey stories, the practice of drawing brings specific narratives to life that propose a double portrait of Beirut, one physical in the materiality of the drawing, and one more psychological, reflecting on the artist's state of mind.

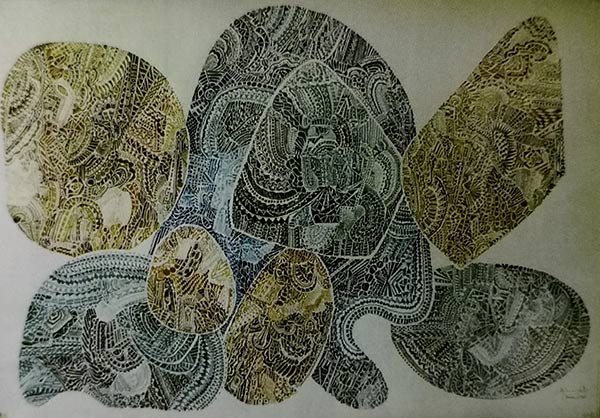

Similarly, in Laure Ghorayeb's work, the act of drawing itself guides the artist in the process of producing her final artwork. Drawing becomes her own world away from the world as she loses herself in this mental exercise. As she sketches, ideas spark off to continue this never-ending process in her drawings.

Consistent with the goal of the NABU museum, this exhibition strives to build new narratives on artistic practices in the region by looking back to the past to learn and foster future creative minds.

I wish to acknowledge that “Traces of Drawings” could not have been conceived without the collaborative efforts of the artists, their families, collectors and gallery owners who entrusted us with carefully displayed parts of their valuable collections for the purpose of making this selection of inspiring drawings, paintings, and sculptures visible to the public. This selection of artworks is exhibited in the hope that its visibility will spark off debates in multiple ways, ones that value artistic production and intellectual progress through the lens of the artists presented in this exhibition.

I am grateful to the founders of the NABU museum and their dynamic team for their endless support in making this event a successful one.

Dr. Yasmine Nachabe Taan - Curator

Daoud Corm - Untitled, 1871, charcoal, pencil and white chalk on paper 59x45 cm - Courtesy and copyright Charles Corm Family

Greta Naufal - Cafe Muller - Tribute do Pina Baush, 1988, Mixed media 112x320 cm - Courtesy and copyright Naufal Greta

Yvette Achkar - Untitled, 1995, color ink on paper 70x100 cm - Courtesy Laure Ghorayeb collection - Copyright The artist and Galerie Janine Rubeiz

Saliba Douaihy - Bedouin, 1949, Oil on canvas 46x36 cm Nabu Museum Collection

Yvette Achkar - Face, 1959, Oil on canvas 46x37 cm - Courtesy and copyright collection Francois Sargologo