Omar Onsi, The Gardener of Epiphanies

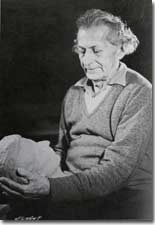

(Photo showing Onsi admiring his sculpture by Youssef Hoyeck, around 1965) - Article copyrighted 1985, The council of the Foreign Economic relations.

Omar Onsi is a figure apart among the “founding fathers” of Lebanese painting, if only for two reasons: first, because his life was so utterly submerged in his art that there is scarcely anything for a biographer to extricate; secondly, because that art itself was wholly blended with the light and landscape of his country, with the humanity of a traditional Lebanon, fixed in portraits, little genre scenes, images of a wonderfully happy land on which alone, as one of its most talented artists, he fastened his gaze and bestowed his heartfelt devotion. Some may argue that all the Lebanese painters of his generation shared practically the same attitude and were similarly moved to find in the humble, endearing, yet colorful and tangy reality of everyday Lebanese life the raw material of their inspiration and even, both ethically and aesthetically, their underlying raison d’ être – and that is true of Moustapha Farroukh, Cesar Gemayel, Saliba Douaihy and a handful of their lesser-known contemporaries, including some, like the Lebano-Argentine Bibi Zoghbé, who were to develop their art abroad, never to return. Nevertheless, the case of Omar Onsi, the state of almost total isolation with which he confronted the grain of his canvasses, the paper of his watercolors – magic casements onto the visible though they were to become – this case of isolation within the ecstasy of the act of painting is sufficiently exemplary to merit being stressed. The striking serenity of his face bore witness to this solitude: the limpidity of his gaze remained unaltered through the years, like that of a boy never returned from a childhood journey of discovery and never disenchanted with its marvels. A critic wrote of him in 1945: “You would think he was staring into the eye of a bracing wind”. And indeed – as all those who knew him will confirm – there was in the leanness of the man, those delicate yet bony features on which, in time, age was to inscribe a tracery of sensitive wrinkles, in his attitude, which was self-assured in its very modesty, in the slight flutter of the voice as it seemed to hesitate on the threshold of the right word – a voice which he never raised above a “sotto voce”, as if fearing to disturb some watching deity or some omnipresent music audible to himself alone – there was in the entire physique of Omar Onsi that shyness, self-effacement of one who is the custodian of a secret far greater than himself, a secret he may let out only in snatches, in statements of oil or watercolor slowly peeled from the contemplative underlay of the artist: hypnotic utterances of which he is but half the author, which it is for the viewer confronting him to complete from his own inmost store of rêverie. And Omar Onsi’s secret was precisely this: that the world, however beautiful, remained impenetrable behind the most breathtaking signs of its beauty, so that it was the task of the artist to make himself as transparent, as evasive, as attenuated” as possible if he truly wished to transcend appearances and capture, if only for an instant, the eternally withdrawn essence of the visible. Hence – one may suppose – Onsi’s preferences and, quite early on, his passion for that lightened form of plastic expression, watercolor, the handling of which medium is surely an art of pouncing upon the instant, of rapture in a sense. We can see for example how Onsi, with increasing mastery, makes use of this technique to recreate with a few deft strokes, fixing both line and color at a glance, the transient miracles of light on a pyramid of red roofs or a hillside of silvery olive-trees, extracting the lurking sparkle from the even daylight as a fisherman of ‘Ain-Mreisseh jerks a fish from the water. It will of course be necessary to consider in greater detail all these technical problems arising from the painter’s conception of his dialogue with the universe as a wild, uncircumscribable force which only an artist’s dogged patience may, on rare occasions, succeed in taming for the duration of a glance. And we shall also be noting how greatly the habit of watercolor influenced Onsi’s handling of oil paint, how, as he, with ever more felicity, explored the virtues of under-statement, his caressing brush turned the oil-painting into simply a more heavily-charged watercolor, one which, without being really weighed down, shed less of the inevitable materiality of the world and its light – for it must be realized that light too, and here we have one of the main lessons to be learned from his canvasses, is material: a matter it was up to Onsi, having for once discarded his diaphanous net, to snare as best he could.

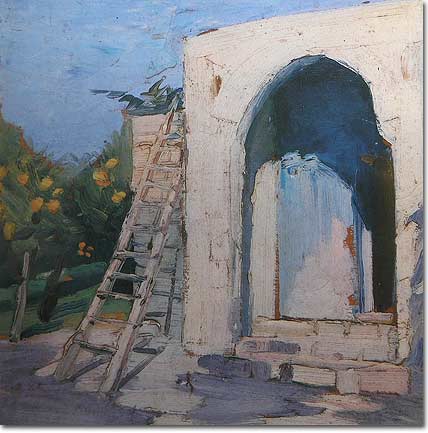

Orange Grove in Sidon, Oil, 39.5 x 31.5 cm

Collection Mrs Haya Onsi Tabbara

Before venturing further into the exploration of Onsi’s themes and techniques, let us look at the few availabledetails of his life and consider the historical circumstances which gave rise to his vocation and ran parallel to its fulfillment.

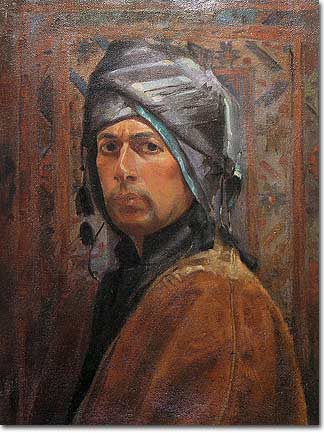

Self Portrait with Turban, Oil, 64 x 48 cm

Collection Mrs. Bouchra Onsi

Omar Onsi was born in Beirut in 1901, into an old Sunni Muslim family. This fact is not without its importance, in that, for reasons of cultural vocation lined to the secret springs of the aesthetic imagination and the way they function, the plastic arts of a figurative kind had up to then belonged rather to the Christian tradition in the country. Christianity being of its nature a consumer and hence and inventor of images. At a time when Islam generally found an outlet for its creativity in other fields and styles than those of figurative painting, Christian Lebanese artists (who, more often than not, were simply inspired artisans) went on repeating in church and monastery the gestures of a “creative” depiction entirely devoted to worship and ritual. Their productions were, it must be said, of somewhat limited interest from the artistic point of view, yet it is only right to pay their due meed of tribute to those humbler and for the most part anonymous picture-makers who preserved the tradition for century after century. However, things began to move, the pace to quicken, in the mid-nineteenth century with what Salah Stétié, in his essay “Par l’amour et par l’image” (Introduction to ‘Cent ans d’art plastique au Liban, 1880-1980, Editions R. Chahine, Beirut, 1982), has described as the “désenclavement” of Lebanon:

“Then the Lebanese began to open their eyes to the outside world,” Stétié writes, “as their country ceased to be an enclave and as many of them felt […] the stirrings of a national awareness. Thus the opening of their minds to that outside world, whether from the political or the cultural point of view, is bound up with their rejection of the irksome Ottoman presence in the region as a whole and, more particularly, in their own native mountains and plains. As one may observe day by day in the interminable struggle of dominated peoples against their dominators, the recovery of an identity is in large measure affected through the expression of the former’s determination not to be what the latter would have it be. Against the deliberate perversion of their image in the distorting mirror satanically thrust before them, they struggle to reassemble the atoms of their own true being and make sure that their proper reflection resurfaces in the world. Yearning for the time when they could ‘to their own selves be true’, the Lebanese were destined to become, throughout a Near East subjected to a capricious alien rule, the reawakeners of the Arabic language and Arab civilization, shrouded as they had been for so long by Osmanli imperialism. Thus was born the “nahda”, the renascence, which – through all circumstantial guises and disguises – was first and foremost the resurrection of the basic cultural identity. And it was by a tenacious determination to rediscover itself in a cultural identity which was original at any rate, if not primeval, that Lebanon was, in parallel with the “nahda”, to venture into the field of art. As tools to assist in the realization of that identity, therefore, Lebanon was to have at hand the painter’s brush, the sculptor’s chisel, and these, quite apart from the achievements of each finished work, were to work away at shaping the features of a people, a nation, or at lending them the colors of life, so that little by little they were to emerge from indecision and stand forth.

Path to the Artist's Home, Oil, 59 x 71 cm, Collection Mrs. Bouchra Onsi

Bourj Abu Haydar, Beirut, Oil, 53 x 63 cm, Collection Mr Mansour Onsi

This quotation should serve to situate within its overall context the adventure of Lebanese art at its earliest beginnings, an adventure which even in its latest achievements has never ceased to be a quest for identity: be it the identity of the painter, sculptor, poet who, each with his own means and vocabulary, endeavor to define the particular nature of their relationship to the world, or the identity of the group to which the artist belongs, of that human community from which he detaches himself like a pathfinder and which more or less consciously expects him to raise it to the dignity of self-formulation that essential, existential formulation by which one learns to know and recognize oneself in one’s difference and, this difference being a value, to do one’s utmost to preserve that value, since it is no added attribute, no superfluous and reversible luxury, but one’s base, foundation raison d’être . And here, no doubt, we have the explanation and justification of the fact that all the pioneers of Lebanese painting turned passionately their dazzled and loving gaze on the living realities they discovered about them: men, women and children of the native soil, the light and the landscapes, the customs and homes, the costumes and faces, shapes and sights, striving with the infinite pains of loving fidelity to reconstitute them in their pictures. But who were the «masters» a work of whom young Onsi could have studied here and there? Did his eyes ever light upon some vaguely Italianate canvas of his forebear Kanaan Dib, from Dlepta (Jdaidet Ghazir)? Did he ever in his childhood come across some little picture by Ibrahim Sarabiyyé of Beirut (at a time - 1850 - when that city was all crooked alleys and verdant orchards): some portrait touching in its clumsiness, some hillside scene, or some seascape actually quite subtle with its tangle of tartana boats in what was one day to become known as the Old Port? Did he ever have in his hands some colored or charcoal drawing by Sheikh Ibrahim Yazigi, who was also a most accomplished calligrapher? What indeed, of that small, scattered, dreamy band who, last century, marked the beginnings of Lebanese graphic art - while at the same time the Bonfils dynasty, in particular, began to develop the technique of photography – what manifestations or vestiges preserved here or there could in the early years of this century have nourished the rêverie of a self-questing adolescent and triggered the spark of inner illumination? Well, there was Démechkié, of whom only one painting (of the British battleship «Victoria» sinking off Tripoli) is known, there were Hassan Tannir Mohammed Said mer’i of Basta, who was to emigrate and end his days in America, Najib Fayyad of Ashrafieh, Abdallah Matar from Lehfed, and even a medical officer of the Ottoman navy, Ibrahim Najjar, who came from Deir el-Qamar and pursued the arts of painting and drawing in his leisure hours. There were above all two more important painters who both. After promising beginnings in Lebanon, took the path of exile, one Salim Haddad of Abey, making a name for himself as a portrait-painter in Egypt while the other, Najib Bakhazi of Ashrafiyeh (then an autonomous township), took himself off to Russia, where his trail has grown cold…

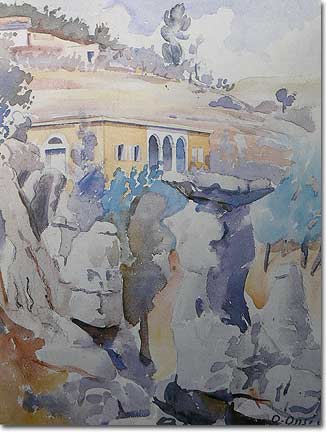

House on Rocks at Ain El Tannour, Meyrouba

Watercolor, 39 x 30 cm, collection Mr. Tammam Salam

All in all, then, at the formative period of the young Onsi - who bore the same name, Omar, as his paternal grandfather, a scholarly poet well known in cultured Beiruti circles -, the art of painting was already an accepted feature of Lebanese society. A number of artists, known and appreciated if only by the minority, were exercising their various talents and, in certain cases, had opened a studio where they transmitted as teachers what they had gleaned from frequenting the academies and museums of Rome, Paris, London or – even so early – New York. One day in 1870 a twelve-year-old Daoud Corm went off to Rome, where he perfected his training; he was to become eventually the favored portraitist of the prominent families of Lebanon, Syria and Egypt, and was also to paint full-length portraits of Pope Pius IX, the Belgian royal family, and the princes of the Khedival court, Tawfiq I and Abbas II. Cairo was likewise the setting of Habib Srour’s career after his pilgrimage to Rome , and before his return to Beirut where he taught drawing at the Sultan’s Osmanli College and opened a studio attended not only by Omar Onsi but also by Moustafa Farroukh, Saliba Douaihy and Rachid Wehbé. Gibran Khalil Gibran, before casting anchor in new York, spent two years in Paris, where for two years he followed the teaching of the greatest sculptor of the age, Rodin, where he surely encountered, apart from Paul Claudel’s sister Camille - in whom we are now coming to recognize a sculptor of genius - the great German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who was busy both with the “Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge” that were to bring him fame and with a biographical approach to the mighty creator of the «Gate of Hell». Youssef Hoyeck, a native of Helta (Batroun), after the obligatory stay in Rome – the fascinating capital of a tired classical art then on the brink of academicism -, chose to settle in Paris, attending not Rodin’s studio but one nearly as illustrious, that of Bourdelle (just as, half a century later. Michel Basbous was to work as the assistant of Zadkine at his studio in the Rue d’Assas) But the greatest traveler of them all was Khalil Saleeby, zigzagging from Beirut to Edinburgh, Edinburgh to New York, then back to Edinburgh and on to London – whither another Lebanese Saliba Douaihy had found his way from New York – and eventually returning to Beirut where, in 1920, he welcomed as friend and pupil, among others, Omar Onsi, who was to declare how much he learned from Saleeby, especially in the art catching the light, and César Gemyel, a man torn between his exacting studies to be a pharmacist and his eagerness to be splashing colors.

Landscape in Alsace, France, Watercolor (Aquarelle)

33.5 x 52 cm, collection Mrs Haya Onsi Tabbara

Thus technically qualified, and already a master of practically every effect his inspiration required. Omar Onsi was invited to Trans Jordan , where for five years he taught the groundwork of his art to royal pupils, including an aunt of King Hussein’s who was subsequently to make quite a name for herself as a painter in Paris. This stay in a semi-parched country left its most decisive mark on the young Lebanese artist through his encounter with the desert, with its tawny hues, its crisp blue shadows, and the delicate sensuousness of its modulations at once arid and refined the lyric dryness of its light. Onsi’s palette was never to forget that stern and sober lesson; throughout his work as it unfolded he was to preserve, of that fundamental experience, a taste for uncluttered severity, an intuition of the «genius loci» as abstracted from the light: these were to underpin the plastic vocabulary of Onsi even where he gave vent to his love of the subject in lively, colorful abandon.

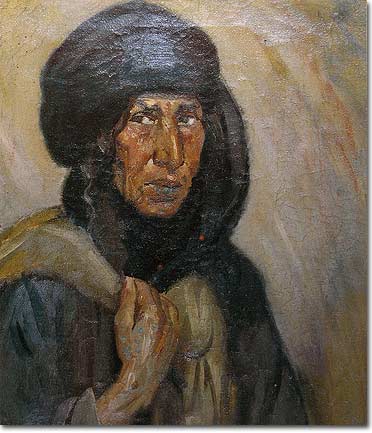

The witch (Portrait of a Bedouin), Oil, 63 x 47 cm, collection Mrs Bouchra Onsi

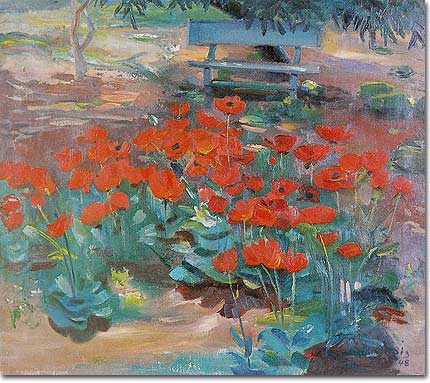

When, in 1928, Onsi went to Paris to continue his training at the Julian Academy , we can be sure that he was duly dazzled by the impressionists in the galleries, yet his palette was already, in the main, complete. He returned to Beirut in 1931 and, in his wonderful old Lebanese house overlooking the sea amid the russet dunes, lived from that time on for painting, for painting only, with his foreign wife assisting him to accomplish his artistic destiny, and surrounded by aloe shrubs, all kinds of flowers and, above all, by masses of those rhododendrons which he loved so much his whole life long and depicted over and over again in his watercolors. His garden contained not only flowers but also a little enclosure of tame gazelles, whose graceful charm à la Matisse his brush could equally evoke. His visitors comprised a handful of faithful friends, some – often European – admirers, and a few young painters who were not however his pupils, for he wished to remain as solitary as possible, even if his obliging courtesy and vigilant attention made of him an assiduous visitor of «vernissages» and exhibitions where, after careful observation of the artist’s work, he would pass a brief comment that was never lacking in sensitivity and generosity. Pure spirit that he was, Omar Onsi had no enemies.

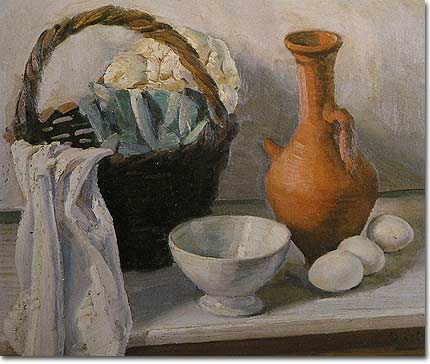

Still Life with Cauliflower, Oil, 37.5 x 45 cm, collection Dr. Hassan Rifai

One great friend he had, however, who was also one of his admirers and with whom, as the years rolled by, he developed a dialogue of the deepest kind. This friend was a painter too, an excellent painter whose peregrinations had led him from his native Normandy to Beirut , where he settled in 1934 and was to end his days some forty years later, having meanwhile become so Lebanese as to dedicate to our country – in that little sea lapped triple-arched house of his at «Ain Mreisseh- the whole of his talent, his spirit of initiative and discovery, his teachings also, ranging from the art of mixing colors to the philosophy of art, from the analysis of forms (his painting swung between the figurative and what you might call not so much the abstract as the «constructive») to the intuition of that poetry without which those forms would remain lifeless. Yes, Georges Cyr - that was his name - was by his example and wide – ranging activity one of the most effective ferments in the emergence of Lebanon’s new sensitivity to the plastic arts. His influence spread far and wide during the period of the French mandate and beyond, when he decided once and for all to adopt the country that had adopted him. A friend of Albert Guillaumin, Othon Friesz and Raoul Dufy, he left behind everything that, had he remained to work in Paris, would have ensured his being exhibited at the leading salons and museums – from which his work is however by no means absent. As an extraordinarily deft aquarellist, he too quickly learned to note and denote the strong and supple accents of our landscape and humanity in all their most meaningful radiance. Like Onsi, he was a poet of light, of our country’s light, and one day it will be a pleasant task to try and determine whether it was he or Onsi who most influenced the other in lightness of touch. But it was doubtless a two-way process: if Cyr remains the «airier» Onsi is the more substantial of the two, the one who more impregnates his paper with color, under girding it as it were with the experience of oils, just as, conversely, he took advantage of his familiarity with watercolor to attenuate as far as possible the materiality of his canvasses and thus to simplify and lighten them. Actually, Georges Cyr, in 1950, devoted a three-or-four page essay to Omar Onsi in the third album of the series «Les peintres du Liban» published by les Editions du Murex under the imprint of the Imprimerie Catholique de Beyrouth. At the conclusion of this study he admits in the following terms his preference for the subject’s watercolors: «what wins one over completely in the work of this painter is his watercolors, doubtless because they are less calculated and more spontaneously betray their author’s sensitivity to the enchantment of those colors adorning trees, houses, men and animals. He gathers up full swatches of color like one plucking flowers, and arranges them into a nosegay of tender souvenirs».

Wid flowers, watercolor, 40 x 60 cm, collection Mrs. Haya Onsi Tabbara

And Cyr had begun his study thus: «Omar Onsi is a poet. That should suffice to rank among the best painters, for without that inner life reflected on the surface on the picture in the harmony of shapes and colors there is no work of art but only painted matter. He is a poet in that every vision of the outer world prompts him to rethink that world and imagine its potential relationship to humanity».

The tattooing, watercolor, 33 x 43 cm, collection Mr Mansour Onsi

From all the above it is easy to deduce what themes were to inspire Omar Onsi in painting after painting. A born colorist, his spontaneous bent was to go after color wherever it was to be found, devoting more in his work to the plenitude «of» color and the plenitude of form achieved “through” color than to the delineation and promise of form achieved through the draughts-man’s simplifying stroke. Drawing «defines»: it extracts a fragment of the world and enhances it by detaching it from all the rest. Color, even when it contrasts - indeed, above all when it contrasts -, pursues the dream of a fundamental unity shrouded in the glancing motley of appearances. What line divides, color knits together again in its substantive nostalgia. And the world around Omar Onsi, the Lebanon of his time, was a kind of Paradise , of Primal Garden , every blissful instant of which he thirsted to enjoy. This is how Georges Cyr (yet again - but how acute a witness!) described the Lebanon of the «thirties in an article from «L’Orient littéraire » of 20 January 1962. «It was in the early days of 1934. I arrived in an old tramp steamer spitting fire from its smokestack... It was then Beirut advanced towards me. I can still see the image that then rose in my mind of a hand extended above the waves to offer me its white houses nestling in the greenery of its garden’s almond-trees. In the background, gracefully stretched out in an attitude of repose, the mountains offered the model of its body veiled in rosy clouds.

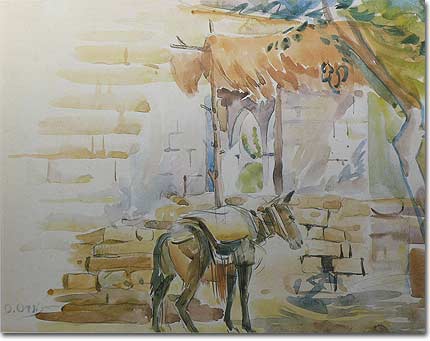

Mule in front of an "Irzal", watercolor, 34 x 47 cm,

collection Mr. Jihad Abillamah

The pleasure was sensual. To be sure, but one which penetrated to the unconscious, releasing images of universal harmony, free flights of fancy, like the state of mind created by the impact of a striking line of verse».

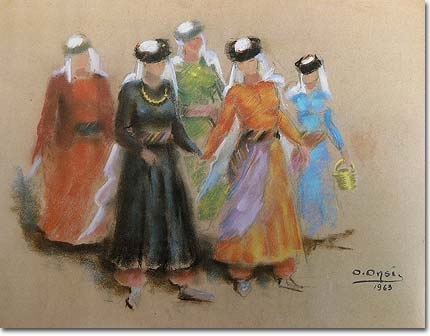

Kurd Women in Beirut, pastel, 48 x 63 cm, collection Dr, Hassan Rifai

Cyr went on to write: «I arrived, I had my car unloaded in the mild sunshine, and off I drove along the first road I encountered. As I later learned, this was the road to Sidon, and three I remember I had the joy, after criss-crossing the humpbacked alleyways, of coming upon the little port where fisherman squatting on coils of rope were tossing shuttles through the torn meshes of their nets. They chatted, joked and laughed as they worked, but I of course knew nothing of their language. I was moved nevertheless to smile, but not at their jests: I was smiling at that magnificent sunshine of Lebanon which quite stunned me – but was good enough to extend me its friendly welcome throughout the first days of my new life. […] Form an indescribable mass of humanity there darted back and forth, yelling, running, grabbing each other, some dozens perhaps hundreds of children, clothed in an unbelievable assortment of colors, a patchwork of reds, yellows, greens and other hues. Here and there came into view the outline of a woman in a white shawl, a colored apron and a long thick grown that swept up clouds of dust from the wayside […] it all dazzled and enchanted me. Like a real tourist, I was seduced by all those Oriental frills that, drenched in sunlight, seem to burst into all the colors of a marvelous picture. Later, I was to set aside those deluding fripperies in order to get at the real soul of Lebanon , and still wonder at its supple fascination – but that is another story.”

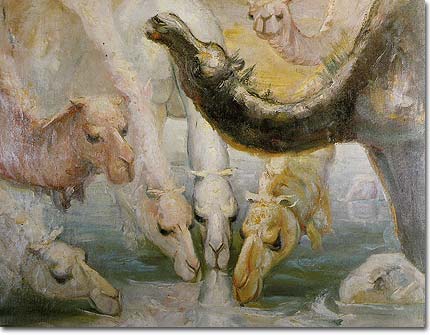

Camels at the drinking through, oil, 80 x 99 cm, collection Dr. Hassan Rifai

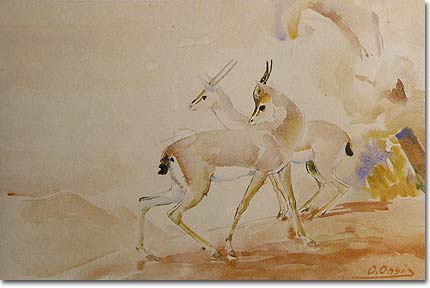

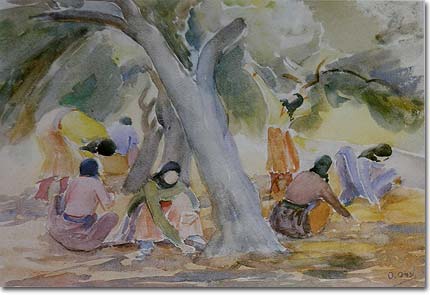

Yes, the surface charm of that Lebanon was so powerful that Onsi, like the other painters of his generation, had, you would think, merely to dip into what lay around him in order to grasp the element of his quest, his conquest. Quest for identity? Conquest of the world’s substance and secret? So easy was the relationship of the artist to his environment that it all seemed there within a hand’s grasp or at the tip of his brush. He simply had to breathe on the canvas or paper, let the color run over its white surface, for the signs of an unmistakable identity to appear and celebrate, brushstroke after stroke, the happiness of existence: in this eruption of anemones, those round soft peaches mauve from the mere pleasure of their dialogue with a pink and white tablecloth and a blue vase, those white-clad women seeming to swivel with their softy gleaming jars on their way back from the village fountain, that Bedouin woman (an inescapable subject at which all the painters of that time tried their hand) in whom, rather à la Manet with a touch of fauvism, the black hues of the turban are galvanized into self-assertion by the intense reds and blues of her costume, with her tattoo marks adding their note of green to the concert; then there are that admirably rhythmic aloe-bush carved out, as it were, by light against an almost linear background in which the outline of trees may be divined, the little fishing harbor on which night has already begun to cast its pall, embowered in a near-black blue wherein the debris of a recent sun lies near at hand in tints of violet, farther off in tints of yellow and red; then this bitter, bistre landscape lying prone before a distant sea swept by a lighter blue we know to be the sky; these two gazelles, reclining yet brightly alert with all the feminine charm of their refinement, and counter pointing the nearby ranks of aloes; these nudes as sensitive as if their soft tawny skins were receiving the light of earth’s first day; those studies in which the painter’s spontaneity in no way diminishes his gift of observation or innate sense of the finest nuance.

Two Gazelles, watercolor, 33 x 48 cm, collection Mr Samir Abillamah

The color of Onsi’s paintings is naively, arrestingly sensual. Welling up with a slightly muffled force, as if reluctant to break its tie with an inner secret, as if, nevertheless, it were the very substance of appearances, it seems to tear itself away in strips from a hidden energy that seeks to retain those strips in order, in time, to restore them to their pure vocation: that vocation being to vanish into the daydream of happiness that gave rise to them, so as to leave no room but for happiness, as happens when, at another level of artistic creation and in accordance with other parameters, one contemplates a life-saturated painting by Matisse.

The hind, watercolor, 31 x 47 cm, collection Mr. Jihad Abillamah

Onsi’s art eschews all excess, faithful as it is therein to the nature of its creator, to the very nature of the inspiration deployed, each quite simply – strangely – harmonious with each other. Indeed, “harmony” must be the keyword to defining the specific character of Onsi. You could call him a musician, for what it is worth to speak of one art in terms of another: a musician, in particular, in his use of watercolor. A would-be charmer of the blank sheet, conjuring up from it with infinite delicacy the tokens of a style, he remains happily to all the “given”, to that simple treasure of the landscape which has practically dissolved into the light – faithful also to all supple, spontaneously poetic figures: boats, girls, trees. Two strokes suffice this Onsi to enliven a pine tree-top with a caroling of pure color. This is a weightless Onsi, a son of air, the inventor of a new style of arabesque. The properties be borrows from music are the fluidity that distinguishes his work, the transparency of his resolutions, one might rather say their “crystallization”, a visible shrinking from over-statement whereby the invisible is enticed into expression. Indeed, the entire art of the watercolorist resides at the meeting-point of the temptations to crystallize – which cannot avoid some effect of “abstraction”, be it ever so small – and sensitivity to that enticement which demands a great degree of inner openness and response. That openness “furnishes” the blank sheet with empty spaces, spaces not merely blank but of a magnetic emptiness more pregnant than plenitude itself.

Olive-Picking, watercolor, 34 x 49 cm, collection Mr. Farouk Abillamah

Plenitude is the culmination of a long tradition of health. Is health a value in the plastic arts? Yes, replies the entire oeuvre of Omar Onsi. It is healthy as a plant or woman may be: more moving for being healthy in their innate delicacy. Their divined inner frailty becomes the more treasurable thereby.

Poppies, oil, 59 x 72.5 cm, collection H.E. Saeb Salam

When Omar Onsi died, on 3 June 1969 , there died with him a tender of the garden of epiphanies, a painter for whom Lebanon was a love story, and a poet whose colorful dreams belong to the most precious part of our heritage.

Saleh Stéitié